Bridges, poetry and lockdown

- colinfell6

- May 12, 2020

- 4 min read

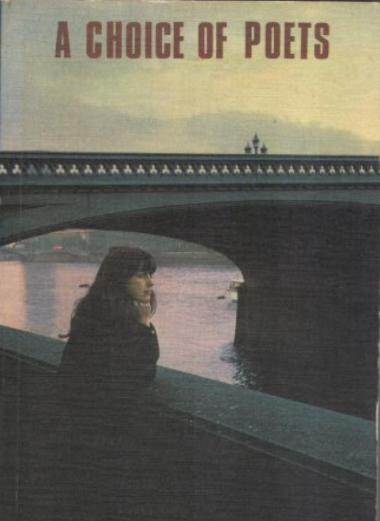

When I was a dull, sulky, introverted 15 year old schoolboy, we were given a book called A Choice of Poets. Poetry, surprising as it might seem to me now, lit few fires in my teenage soul- I found my poetry in the arc of a football as it curved into the corner of a net, or, even more seductively, in the mysteriously attractive, pale, dark haired girl on the cover, leaning pensively on a balustrade in front of the Thames, thinking profoundly poetic thoughts about- well, what? Tides and currents? Love, my fifteen year old heart secretly hoped. The girl was an editorial choice no doubt fuelled by the need to get adolescent males to open the book, and take some sort of interest in its contents. To this day I remember her more than the contents, but one poem that made an impression was Wordsworth’s Upon Westminster Bridge, the pretext for the unmistakeable ironwork looming tastefully behind the girl on the cover. And it’s a poem that has occupied me considerably since then, particularly in these lockdown times, imagining Wordsworth crossing the bridge and gazing down, pensively as the dark haired girl, and admiring this sight “so touching in its majesty”.

Most people’s image of Wordsworth, if they have one at all, is likely to be the old mystic, craggy as the mountains of his native Lake District- but he was a young man before he was an old one. On the morning of July 31st 1802, aged 22, he was travelling to Calais with his sister Dorothy, for a specific purpose- to meet his French lover, Annette Vallon, and their young child, Caroline. It was, potentially, a dangerous journey; the Napoleonic wars had made the continent dangerous and difficult lotion for British travellers in a way which would have seemed hard to comprehend today, at least until the events of the last few years; but Wordsworth was taking advantage of a lull in the fighting. And en route, his carriage stopped for a few moments, upon Westminster Bridge.

Apart from the image of the brooding prophetic poet, the other thing most people know about Wordsworth is that he was the poet of the natural world, with a mistrust and dislike of urban environments- so it’s perhaps surprising to find him here eulogising London, which he’s rude about elsewhere in his writing. So what makes the difference here? Is it something to do with the magical power of bridges, stretching in defiance of gravity over the treacherous spans of moving waters, connecting the unconnectable, poised magically over the gulf beneath? Or is it more that this is a fleeting moment, London caught unawares, still asleep, Wordsworth as a sort of voyeur, an Actaeon peeping longingly at London’s Diana? Wordsworth describes London as wearing “the beauty of the morning like a garment”, one that can be taken off once the moment has passed, and its beauty seems to consist partly in that its buildings “lie/ Open unto the fields, and to the sky…” He’s really describing what Canaletto was painting half a century earlier, when he moved from Venice to London to be closer to his principal market. The streets are largely empty, aside from the occasional fastidiously drawn figure, and nothing impedes the clean aesthetic geometry of architecture and river- and it is of course even more reminiscent of our lockdown cityscapes all over the world, as photographers have rushed to fill social media with records of the eerily empty streets of the City of London, and thousands of other no longer busy metropolises. On some level this appeals to the child in us- cities as toytowns, and to some extent to the utopianists and ecologists- the beau

ty of a world stripped of its polluting, messy people.

Anyone googling Westminster Bridge at the moment is likely to find themselves directed towards the terror attack, perhaps suggesting that even the dark heart of the terrorist has somewhere in its depths an awareness of the power of the bridge. That modern cipher, Google, will also suggest that you checkout stories about members of the public gathering where Wordsworth once contemplated, to clap the heroism of the NHS. The first picture to emerge of this intriguing phenomenon drew criticism for the apparent failure of the crowds to observe social distancing, subsequent images showing people stationed at arithmetically precise distances, solitary and pensive as young Wordsworths. Bridge clappers today have their anxieties, as do we all, and the twenty two year old poet must have had his own profound concerns at the time- the risks of travelling to Napoleonic France, not to mention his apprehensiveness about a forthcoming reunion with his lover and child, complicated additionally by his forthcoming marriage to Mary Hutchinson.

Lockdown has once again focused some minds- mine, anyway, on the enduringly intriguing and suggestive symbol of Westminster Bridge. Connecting the ancient power bases of West London, where the decisions are made, with shabbier, more impoverished Lambeth, where coronavirus will claim more lives, it is itself a metaphor for the country; the juxtaposition of rich and poor, the powerful and the powerless. Perhaps that’s what she was really thinking, that unattainable girl on the cover, all those years ago.

Comments